Archaeology

Lying between Wakefield and Huddersfield, is a fascinating architectural jigsaw puzzle. Apart from the massive west tower, constructed at the end of the Middle Ages, the church is jumble of stonework belonging to various centuries. Some of the earliest fragments built into the present walls date to Norman times. The drawing on the right shows one of these fragments, part of a panel carved on the lintel stone of a Norman doorway. The two animals are the Lamb of God and possibly a lion; the top is missing. Many more pieces of the Norman building , along with several carved grave slabs of the late 12th or 13th century, can be found by carefully examining the inner faces of the walls; the locations of some are marked on the plan.

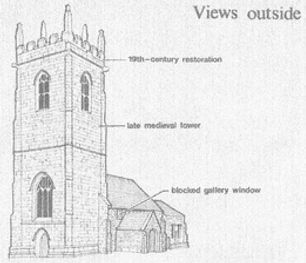

The drawing on the right shows the church's most imposing feature: the massive late medieval tower, which dominates the building. The tower dates from the late 15th or early 16th century; it was erected at a time when many other churches in the region were also being provided with new or renovated west towers. Emley's tower was entirely new; it is built of large , neatly dressed gritstone blocks and has been little altered since. It represents a considerable expense, but we do not know who paid for its construction. The tower probably replaced a small bell-cote, set between two windows on the west wall of the nave. The side of one of these windows can still be seen within the church, by turning to the left just inside the doorway.

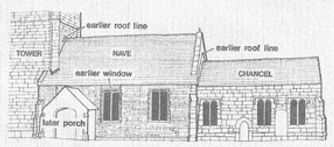

The rest of the church underwent numerous additions, alterations and rebuilding at various times. Many important changes can be seen in the south walls of the nave and chancel, shown on the right. The nave wall was probably built in the 14th or early 15th century; but the rough, uneven stonework and the scattered blocks of the Norman masonry show that it is largely made up of material salvaged from an even earlier church. The windows are 19th century restorations, but they are in fact set within the rectangular frames of older windows; the top of the earlier window on the left can be seen just below the roof eaves.

The roof of the chancel has also been changed considerably: the scar of an earlier, more steeply-pithced roof can be seen in the gable wall of the nave. The core of the chancel wall was built at the same time as the nave; a narrow band of the original walling can still be seen at the junction of the nave and chancel. Later the chancel was refaced, and took on its present appearence. The large, neat gritstone blocks and mouldings on the plinth and buttress - more elaborate than on the nave - are reminiscent of those on the tower. The chancel was probably refaced either at the same time as the tower was built, or soon afterwards. Its windows are in a style of belonging to the late 15th century.

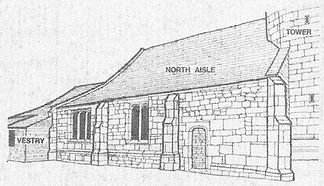

The drawing on the right shows the north aisle of the church. It seems to be a mixture of stonework , much the same kind of mixture as the south wall of the nave. The buttress on the right, the large blocks of stone extending eastwards the the blocked doorway and the doorways itself, all look as though they were built at the same time as the tower.

Above and to the left, the walling stones are smaller and the plinth higher. The buttresses and central window are like those on the south side of the nave and chancel; much of the stonework may have come from the earlier north wall which was largely demolished to make way for the arches between the nave and aisle. The farther aisle window is early 17th century, and the vestry beyond was probably built in the 18th century.

The changes visible in the interior of the church are as varied and complex as those on the outside. The drawing above shows a view from just inside the doorway, looking towards the alter. Probably the earliest walling which can be seen is that between the chancel arch and the north aisle arcade. The walling there is much thicker than the aisle wall which runs westwards from it, so it seems to have been part of the orginal external north wall, which ws reduced in thickness when the north aisle was built in the 15th century.

The aisle was only the first of a series of extensions on the north side of the church. The next was a chapel, opened up to the north of the chancel, in the space now occupied by the organ. An archway leading into it from the north aisle opening into it, from the chancel, is identical in style to the chancel arch; the two were probably inserted at the same time. A further extension is marked bty the eastern archway on the north side of the chancel. This enlargement was made to provide a burial chapel for the Assheton family; the east window of the chapel, though much restored, bears an inscription with the date 1632 - the date of construction. The aisle window visible on the left of the drawing is similar to the east window of the Assheton chapel, and was probably inserted at the same time. The final enlargement, the vestry behind the organ, was built in the 18th century. An earlier blocked window can be seen by its doorway.

To some extent it is possible to identify the doorways and arches from which the carved stones are derived. The reconstruction on the front of this leaflet shows the decorated lintel (or tympanum) built into the nave recess. It probably came from the Norman south doorway. The lintel would have been supported by plain, square-cut jamb-stones; flanking these were columns with round shafts, simple bases and decorated capitals. The round mouldings which now form the sides of the recess are sections of the shafts. One base is built into the nave wall nearby; the other is in the chancel wall, in the surround of the south doorway. A damaged capital of one of these columns is built into the bottom of the masonary pier at the south-west corner of the Assheton chapel. Othe pieces of shaft are larger in diameter; these and some arch stones may have come from the chancel arch of the Norman church.

The north-east corner of the nave may be one of the earliest parts of the church as it stands, but even this contains re-used masonary dating from the 12th century . There are many other pieces of stone from the same period scattered around the walls of the present building. It seems that the earl;iest stone church at Emley was largely demolished in the 14th and 15th centuries, the materials being re-used in the present structure. Much of the Norman stonework is built into the nave wall. The locations of most of the carved stones are shown on the plan. In addition, there are numerous plain facing stones from the same period: these are recognisable by the narrow, diagonal grooves on their surfaces, grooves which are characteristic of the technique used by Norman masons for dressing stones. They are quite different from the tooling marks on the facing stones of the late medieval tower.

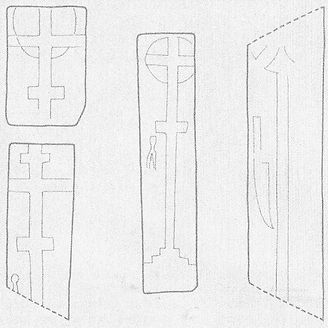

Ten fragments of medieval grave slabs are built into the walls of the nave and chancel. Two can be seen on the outside walls of the chancel; the rest are inside. Most of them have been used to form the lintels, sides and sills of windows, their shape and size being ideal for this purpose. They bear simple, incised designs, mainly crosses with circles round the head, one or more horizontal bars on the shaft and stepped bases. Some also have emblems appropriate to the person formerly buried underneath: pairs of shears, a knife and a sword are represented. They were probably made by local masons in the late 12th or 13th century.

Courtesy and copyright of West Yorkshire Archaeology Service.